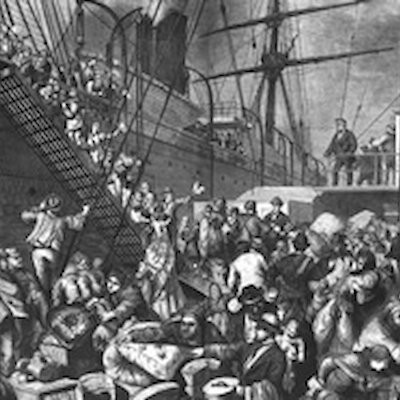

Fair Isle lies between Orkney and mainland Shetland on a major sea route that for centuries has seen sea traffic between Europe and America; this sea route determined the development of Fair Isle’s distinctive knitwear.

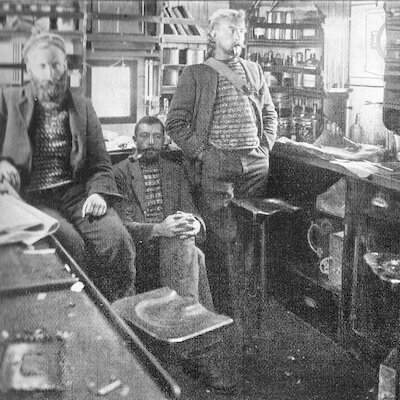

A long tradition of island men who travelled the world on whalers and bartered garments for necessities started the commercialization of Fair Isle knitwear; it was the spirit that, when the men were at sea and weather and darkness kept women and children indoors, spawned spectacular creativity and timeless, infinitely variable, patterns.

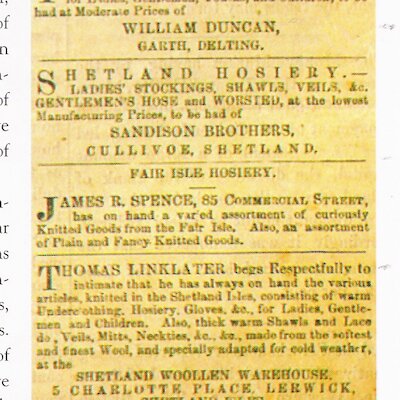

Everything changed in 1845 when Old Norse runrig cultivation was divided into crofts causing a significant decline in living standards on Fair Isle. With poor fishing and crofting seasons, 134 souls had left for Canada by spring 1862. In the same year, The Shetland Advertiser offered a ‘varied assortment of curiously knitted goods from the Fair Isle’…

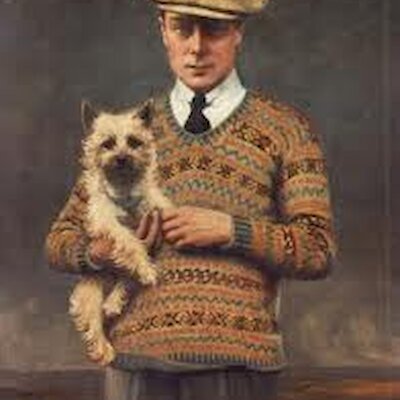

When Queen Victoria died in 1901 and the popularity of Shetland lace fell, the shift from lace knitting to ‘Fair Isle’ knitting had begun. In the 1920s, Stanley Cursiter’s painting ‘The Fair Isle Jumper’ and the Prince of Wales's appearance sporting a Fair Isle jumper while golfing, inspired an unprecedented Fair Isle craze that continued into the 1930s.

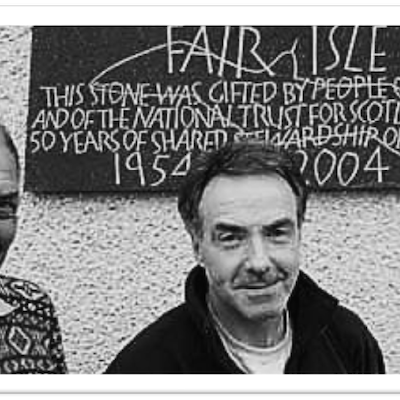

In 1947, George Waterston purchased Fair Isle, started to develop his plan for the island and built a bird observatory. In 1954 the National Trust for Scotland bought the island and secured its protection. Alas, Waterston’s plan of marketing the island goods in Edinburgh and London was never fully realised.

With the 1980s came a Fair Isle trademark. And until 2011, a crafts co-operative took Fair Isle garments from subsistence craft to luxury items on cruise ships.

Meanwhile, centuries-old skills passed from mother to daughter. But, where dozens of women once knitted into the night, only a few knitters remain on an isolated crofting community still untouched by North Sea oil’s influence on Shetland.

'…while she sat till the small hours plying her knitting needless, the produce of which was all she had to depend on for tomorrow’s dinner.'Jessie Saxby,

The Brother’s Sacrifice (about Shetland women; written in 1876)

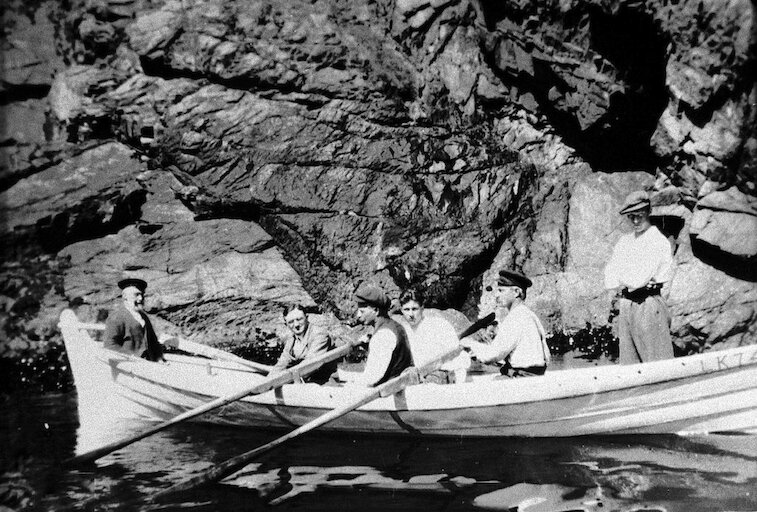

Fair Isle yoals are at the heart of Fair Isle’s relationship with fishing and the barter of produce with passing vessels. Based on Viking craft that once sailed the Atlantic, sturdy little yoals were originally imported from Norway, but have been built on Fair Isle since the mid-nineteenth century.

The island has always depended on the sea. And disaster at sea has always threatened Fair Isle’s mariners – whether they've been fishing for seethe or piltocks, or trading knitwear with passing ships. Around 100 recorded shipwrecks began with Sigurd the Viking in AD 900; the most famous was El Gran Griffon and the most recent was Kedana III in 2001.

Helping shipwrecked sailors once threatened islanders with starvation, but wrecks brought timber for building and tool making on a treeless island. And salvaged sailcloth, copper, lead; chains and wire were invaluable.

Over centuries, the sea has taken scores of islanders’ lives. When Fair Isle’s worst tragedy took eight men in 1897, 29 dependants remained – and Fair Isle’s women sold knitwear to help the families.

The only thing we’re left with is the sea…

'Fair Isle at Sea - thy lovely name

Soft in my ear like music came.

That sea I loved, and once or twice

I touched at isles of Paradise'Robert Louis Stevenson, Fair Isle at Sea.